Accelerated Time and Online Dating

The concept of “Internet time” or “accelerated time” describes how the rapid pace of technological change and instantaneous digital communication compresses traditional time perceptions (Castells, 1996). Since its launch in 2012, Tinder has revolutionised dating by introducing the “swipe” feature (Ranzini & Lutz, 2017). This mechanism encourages rapid decision-making, reflecting the accelerated nature of Internet time. The app’s design caters to a fast-paced lifestyle, where individuals seek immediate gratification and swift connections, often leading to a more transient and less committed approach to processes of dating.

Manuel Castells’ notion of “timeless time” further elucidates how the digital age disrupts linear, clock-based time, leading to fragmented and irregular time experiences (Castells, 1996). The proliferation of messaging apps and social media platforms facilitates continuous but sporadic interactions, altering the depth and quality of human connections.

Online dating typically involves several stages: creating a profile, matching, messaging, and meeting in person. Success in online dating varies but generally involves face-to-face meetings, whether for casual encounters or long-term relationships (Ellison et al., 2006).

Early online dating sites, like Match in the mid-1990s, resembled personal ads where users clicked through profiles (Mathews, 1965). However, too many options can overwhelm users, leading to less satisfaction and poorer choices (Finkel et al., 2012; Schwartz, 2004). This phenomenon, known as choice overload, was demonstrated by Iyengar and Lepper (2000), who found that consumers were more likely to make a purchase when presented with fewer options.

To mitigate choice overload, online dating sites began using compatibility matching algorithms in the early 2000s. These algorithms aimed to narrow the dating pool and improve user satisfaction and engagement (Jung et al., 2021; Sprecher, 2011). Sites like eHarmony and OkCupid were pioneers in this approach. eHarmony’s algorithm, developed by psychologists, matched users based on variables predicting long-term relationship satisfaction (Buckwalter et al., 2004, 2008). OkCupid introduced match percentages based on users’ answers to various questions, allowing for a more personalized matching process (Rudder, 2013).

The Paradox of Choice – only for women, perhaps.

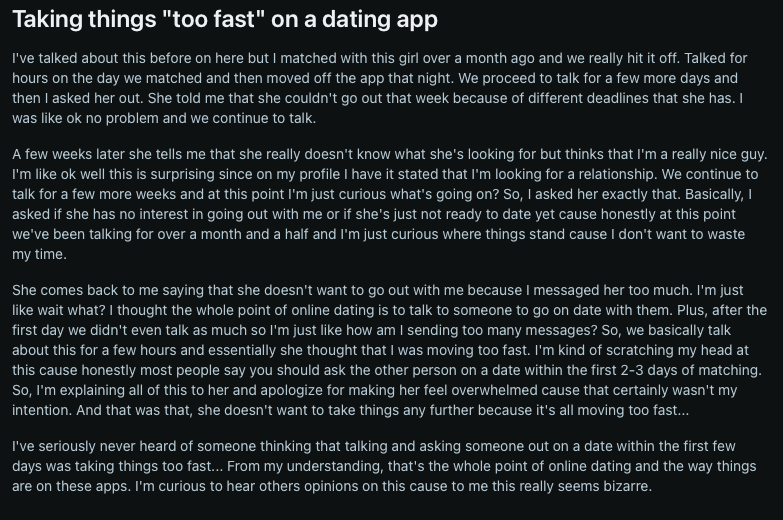

The degree of people’s perception on the duration of time spent on “dating” varies.

Genetic and Biometric Matching

Advanced Genetic Profiling

By 2040, dating apps could employ advanced genetic profiling to match users based on a variety of genetic markers. These markers might include those related to personality traits, mental health predispositions, and physical health indicators. Companies like 23andMe already offer genetic testing that provides insights into ancestry and health risks. Future dating apps could leverage similar technologies to enhance matchmaking by ensuring that couples are genetically compatible, potentially reducing the risk of hereditary diseases (23andMe, 2023).

Immune System Compatibility

The human leukocyte antigen (HLA) complex upon the immune system, is an important part of mate selection. Studies have shown that people are often attracted to those with different HLA genes, which can lead to healthier offspring. This concept is already being explored by services like Pheramor, which uses genetic information to help people find compatible partners (Pheramor, 2023).

Hormone Levels and Emotional States

Biometric data, such as hormone levels, can influence attraction and compatibility. For instance, levels of oxytocin, often called the “love hormone,” play a significant role in bonding and attachment. Future dating apps could measure and analyse hormonal data to match individuals who are biologically predisposed to form strong emotional bonds with each other (Carter, 1998).

Wearable Technology

Wearable devices like smartwatches and fitness trackers are becoming increasingly sophisticated, capable of monitoring various health metrics such as heart rate, sleep patterns, and stress levels. By 2040, dating apps might integrate data from these wearables to assess compatibility. For example, if two people have similar stress responses or sleep patterns, they might be more compatible in terms of lifestyle and daily routines (Apple, 2024).

The Path Forward – Cultural Maturity

In the Possible future of dating in 2050, if current trends continue, the online dating landscape may be inundated with pervasive data collection and analysis. Corporations and governments could wield immense control over personal information, leading to concerns about privacy breaches, manipulation, and the exploitation of user data for profit as seen in previous events.

The Probable future of dating in 2050, influenced by societal responses and regulatory measures, may see a pushback against rampant data surveillance. Stricter privacy laws, enhanced data protection mechanisms, and increased transparency could emerge to address users’ concerns and mitigate the risks associated with data mining. Dating platforms and virtual spaces that adopt more ethical practices prioritising user privacy and consent in data usage would be able to thrive in the ’50 version of what is dating app market. It would probably take a few decades for us to realise that the dating app companies are implementing an addictive system accessible through our gadgets. In 26 years, the system may be so perfectly developed that people are just swiping, screen-staring cyborgs. Best not to forget, it is set up to run for vested interests.

In the Preferable future of dating in 2050, technology is harnessed not just for profit but for sustainable and socially beneficial purposes. Dating platforms in 2050 prioritise the well-being of their users and the planet. These platforms actively promote Solarpunk approach, incorporating features such as carbon footprint tracking for matches, eco-friendly date workshops, and partnerships with environmental organisations.

We will see more niche, more flexible virtual communities within which match-making takes place. In this future, dating apps are more sophisticated in terms of connecting an individual to another. As social acceptance grows, the dynamics on platforms like Grindr and other dating apps would fundamentally change. Users would feel empowered to engage authentically and respectfully, leading to healthier and more meaningful connections. The emphasis on equality would ensure that all users, regardless of their gender, sexuality, race, or background, can find spaces that cater to their unique needs and preferences.

In 2050, the diversity of the online dating sphere would reflect the richness of experiences of all human beings. Social networking services will be designed with inclusivity in mind, making accessible a variety of features that accommodate different lifestyles, preferences, and relationship goals.

By prioritising social justice, creation of a digital dating environment that is as diverse as the society would be possible. This vision of the future promises more empathetic, and interconnected world, where everyone has the opportunity to form meaningful relationships in spaces that celebrate and respect their true selves.

Reference

Bell, Wendell (2004). Foundations of futures studies: human science for a new era: values, objectivity, and the good society (Vol. 2). 1st Edition. Routledge. New York.

Castells, M. (1996). The Rise of the Network Society. Blackwell Publishers.

Coyne, S. M., Stockdale, L., Busby, D., Iverson, B., & Grant, D. M. (2011). “I luv u :)!”: A Descriptive Study of the Media Use of Individuals in Romantic Relationships. Family Relations, 60(2), 150-162.

Hitsch, G. J., Hortaçsu, A., & Ariely, D. (2010). Matching and Sorting in Online Dating. American Economic Review, 100(1), 130-163.

Kapczynski, A., Park, C., & Sampat, B. (2012). Polymorphs and Prodrugs and Salts (Oh My!): An Empirical Analysis of “Secondary” Pharmaceutical Patents. PLoS ONE, 7(12), e49470.

Pollack, A. (2015). Martin Shkreli All but Guts Drug Company’s Research. The New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com

Thompson, C. (2017). Apple Apologizes for iPhone Slowdowns, Offers $29 Battery Replacements. The Verge. Retrieved from https://www.theverge.com

Ranzini, G., & Lutz, C. (2017). Love at First Swipe? Explaining Tinder Self-presentation and Motives. Mobile Media & Communication, 5(1), 80-101.

Schwartz, B. (2004). The Paradox of Choice: Why More is Less. HarperCollins.

Wiener, N. (1948). Cybernetics: Or Control and Communication in the Animal and the Machine. MIT Press.

Leave a comment